This story originally appeared in Mile High Sports Magazine. Read the full digital edition.

He was waiting for me. Never mind I had purposely arrived early. But while grabbing for a door handle at the Red Robin restaurant off Arapahoe and Parker roads in southeast Aurora, a hostess appeared from nowhere, beat me to it, greeted me, seemed to know who I was and said, “He’s waiting for you.”

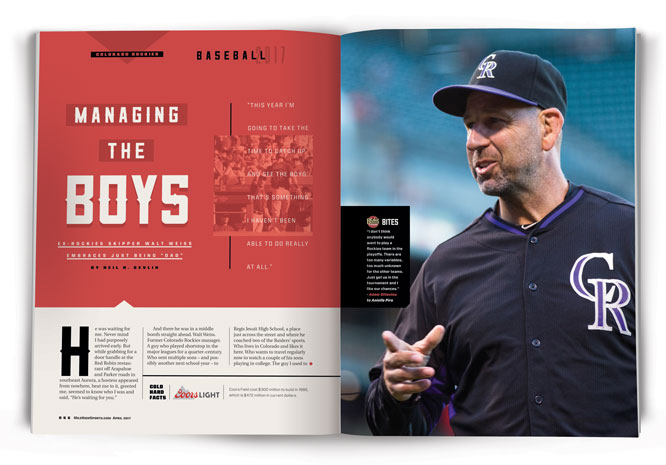

And there he was in a middle booth straight ahead. Walt Weiss. Former Colorado Rockies manager. A guy who played shortstop in the major leagues for a quarter-century. Who sent multiple sons – and possibly another next school year – to Regis Jesuit High School, a place just across the street and where he coached two of the Raiders’ sports. Who lives in Colorado and likes it here. Who wants to travel regularly now to watch a couple of his sons playing in college. The guy I used to tip caps with before first pitch from my family’s seats right behind home plate at Coors Field (and it was pretty cool). And is, despite his high-profile status, a very private man who minds his business, isn’t afraid to smile, and whose considerable competitive nature is rivaled only by his kindness and calm demeanor.

We covered a fair amount of ground in a couple of hours, some of it playing catch-up, other parts I didn’t know.

First, it will be a year off for the now 53-year-old Weiss.

“This year I’m going to take the time to catch up and see the boys,” he said. “That’s something I haven’t been able to do really at all. I’m gonna see my two boys in college, be here with Brock.”

The two boys in college are Brody and Bo. In fact, the meeting with Weiss wouldn’t have happened if Brody hadn’t broken his foot in an accident outside of baseball. Weiss said he would have been away watching him play, “but his college career has been a nightmare; he hasn’t been able to stay healthy.”

From UC-Santa Barbara to Riverside City to now NAIA Westmont, Brody, a former schoolboy star for the Class 5A Raiders here in Colorado, had missed a year and a half with injury, but recreated some excitement earlier this season when he hit a home run in his first at-bat against powerful Lewis & Clark.

At least the father got to see that son play. Bo, a freshman at North Carolina, “is legit; he can throw.” Walt never saw him because of his managerial duties. Bo turned down Stanford in favor of the Tar Heels, where his father played for three years before being drafted in the first round (No. 12 overall) by the Oakland Athletics, and that sits okay with dad.

As for staying in Colorado, it’s where his two other sons come into play. Walt and wife Terri’s oldest, Blake, is involved with Teen Challenge’s 180 Ministries, a rehabilitation center in Denver. Their youngest, Brock, an eighth-grader, recently was accepted at Regis Jesuit.

Brock, his father said, “was a bat boy at Regis when Brody was there, so he’s emotionally attached.”

Of course, Brock plays shortstop and he’s actually a left-handed hitting Weiss – dad was a switch-hitter – and Walt said “we’ve been here 22, 23 years … once they get into high school, you don’t want to uproot them. And with Brock that will happen next year.”

When considering Colorado’s fickle and bizarre spring weather for schoolboy baseball – everything from wind to snow to wind to rain to wind to sleet to wind to gloom and freezing temperatures to gorgeous sunshine and 90-degree first pitches – a possible move doesn’t sound so bad, especially if Weiss is away working with a major league team. He said Terri was left to handle the boys and baseball, and it was trying.

“It’s an extended wind, snowing sideways and kids are playing baseball in it and she definitely doesn’t like it,” Weiss said. “But we have a lot of roots here.”

Still, everyone seemed to be on board with the situation and all that came with it, especially some of the good parts for young male athletes whose father was in charge of a professional sports team.

“The boys, they understood the tradeoff,” Weiss said, “and they got to do some cool things – go on some road trips, be in the clubhouse, Bo got to throw bullpens with major league pitching coaches – a lot of perks, but at the same time you’re trading that for not being around.”

Of course, being away weighed on Weiss. “But I wouldn’t say I felt guilty,” he said, “because not everybody gets a chance to manage in the major leagues.”

And he was used to being away from home. It’s the life of a professional athlete. Suitcases. Hotels. Jets. Not much home cooking. A big-leaguer from September 1987 to October 2000 for four teams, including for the Rockies and the Blake Street Bombers from 1994-97, Weiss’ highlights include being honored as the American League Rookie of the Year in 1988, a World Series champion in 1989, when the Loma Prieta earthquake hit, and being named an All-Star in 1998.

Weiss was definitely more glove than bat with a career batting average of .258 and 25 home runs, but his blue-collar, cerebral approach to athletics was better than any group of career numbers. He’s aware that more than just casual fans remain convinced he jumped straight from Regis Jesuit High to Rockies manager.

Not so.

“The thing at Regis was, I volunteered time and wasn’t like it was a career move,” Weiss said. “If anything, I coached football for four years at Regis and I was more of a football coach.”

In fact, Weiss said, “[Coaching] was a part of me, and I got to dabble as a special assistant.”

For seven years with the Rockies, from 2002 to 2008, Weiss found himself getting involved beyond the actual game that day or night “and it got the wheels spinning that I could do this … it’s not like I was pursuing this.”

Getting involved beyond making out the lineup card proved invaluable in a seven-year run, nuts and bolts Weiss had previously been unfamiliar with, and he ravenously sucked it up like a Dyson, but said he “stepped away for a few years. The boys had gotten older.”

He became the head coach of Regis Jesuit baseball after serving as an assistant, even making the 5A semifinals, but when Jim Tracy resigned, guess who got a phone call?

“It caught me completely off guard,” Weiss said.

He seemed as surprised as anyone in Denver or who follows big-league ball. It literally was a whole new ballgame. He made the decisions. He answered the questions. He got some of the praise when it went well for the team. And – like it or not – he had plenty of criticism thrown his way.

“Yeah, I knew when I signed up; I knew the nature of the business, knew what it was,” Weiss said.

The Rockies were 283-365 in his four years, topped by the past season’s 75-87. Clearly, he had the respect of his players. The array of feelings in the Coors stands and among those watching on television or listening on the radio ranged from a shrewd move in landing a budding, brilliant baseball man to “what the hell were the Rockies doing in bringing up some high-school coach?” Was he in over his head, or was he relegated to firing blanks?

Weiss won’t use injuries or anything else as an excuse or apology.

He even was made fun of for his slow walk to the mound when discussing strategy or to change a pitcher. The running joke was that you could make a sandwich and eat it before he reached the mound, or that he had done it so much that he was worn out.

In fact, he suffered a gruesome injury. June 6, 1991. Against Milwaukee. Think about Joe Theismann’s injury that’s still all over the Internet. Weiss lunged for first base and rolled his left ankle. His left fibula actually came through the bottom of his leg. Only skin was holding it on and a doctor couldn’t believe the bone didn’t break.

“There was so much blood,” Weiss said, “that the grounds crew had to use Diamond Dry (ordinarily used during rain showers) and I had to have a blood transfusion.” A friend from North Carolina, Harris Barton, a San Francisco 49ers offensive tackle who was All-Pro and would be a three-time Super Bowl champion, was sitting close to the field and threw up while medical personnel tried to deal with Weiss. “And this was a big, 320-pound lineman!” Weiss sad.

The doctor also told Weiss that if the injury had occurred 15 years earlier, he probably would have faced amputation. “I saw him five years later in the dugout during batting practice,” Weiss said. “We say hello, give each other a hug and he said, ‘You’re not supposed to be here. You were never supposed to play again.’”

As for his end with the Rockies, Einstein’s wit wasn’t required to see it coming. Weiss knew he wasn’t in the plans of new general manager Jeff Bridich and his contract was about to expire. He said he showed up early for his final game, got with owner Dick Monfort and told him he “was done.” Weiss said Monfort protested, but no matter.

A popular player and manager for the Rockies who also had the respect of the likes of superlative third baseman Nolan Arenado, was gone. Weiss refuses to whine or point fingers. He got a chance. He worked at it. He accepts the results. And he’s grateful.

“I got an opportunity there to do something not many people get to do,” he said. “I enjoyed it most of the time. I loved the connection with the players and staff.”

Working for a common goal, growing together, dealing with the good and bad – Weiss said he embraced all of it. He said he brought in Special Ops and SEALs to address his guys “as the best model of a team we have, literally living and dying for each other. To give them that perspective is very special.”

Is he happy?

“Yeah, shoot, man, it has been a great run for me. I never thought I’d play in the big leagues, and I’ve been there 24 years and managed … it’s something I never dreamed of doing,” he said.

So despite his missing spring training and not coaching on at least the high-school level, Weiss said he’s “good,” eager to see his sons here and out of state, and awaits his next move.

“An adjustment? It hasn’t been that bad,” he said. “I’ve been staying busy and haven’t really paid attention [to the big leagues], to be honest. I’m sure I’ll watch and have an idea of what’s going on.”

In between being a dad.