This story originally appeared in Mile High Sports Magazine. Read the full digital edition here.

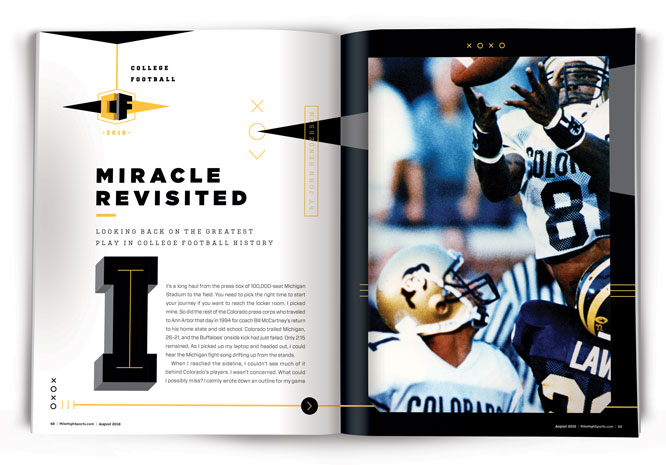

It’s a long haul from the press box of 100,000-seat Michigan Stadium to the field. You need to pick the right time to start your journey if you want to reach the locker room. I picked mine. So did the rest of the Colorado press corps who traveled to Ann Arbor that day in 1994 for coach Bill McCartney’s return to his home state and old school. Colorado trailed Michigan, 26-21, and the Buffaloes’ onside kick had just failed. Only 2:15 remained. As I picked up my laptop and headed out, I could hear the Michigan fight song drifting up from the stands.

When I reached the sideline, I couldn’t see much of it behind Colorado’s players. I wasn’t concerned. What could I possibly miss? I calmly wrote down an outline for my game story: Let’s see. No. 7 Colorado’s comeback falls short at No. 4 Michigan. Three Colorado fumbles negate nearly 450 yards of total offense. Sidebar: McCartney’s not-so-happy homecoming.

Little did I know, while I scribbled in my notepad, receivers coach Rick Neuheisel was scribbling in the dirt. What was about to unfold before me would be the most remarkable comeback in Colorado history, capped by a play many said was the most amazing in college football history.

After 22 years, the “Miracle at Michigan” remains not only in the forefront of Colorado lore but college football’s as well. Colorado returns to Michigan Sept. 17, the place where one play defined two players forever and sent two coaches’ farewell seasons in different directions.

“It was lucky,” McCartney said recently. “You have to be lucky.”

True, but what went into the play was months of preparation and the remarkable athletic ability of two players whose post-football lives have been nearly as successful as the play that defined them.

The weight of the moment had no effect on me. I had quit writing play-by-play. Colorado had stopped Michigan on downs and fair caught a punt on its 15-yard line. The Buffaloes had to go 85 yards in 15 seconds. They had no timeouts. They knew Kordell Stewart couldn’t throw the ball 85 yards.

Sixty? Yes.

“On the sideline, I drew up another play, literally in the dirt, because we only had one play with four wide receivers,” said Neuheisel, now a SEC commentator for CBS and a radio talk show host on SiriusXM Channel 84. “I called it ‘Michael.’”

Using four wide receivers, they had Michael Westbrook, the all-Big Eight receiver from ’92, run a vertical route about 15-20 yards. And that’s all.

“I said, ‘Michael, you have to fall down,’” Neuheisel said. “You can’t run with it. You don’t have time.”

Westbrook did what he was told. He caught the pass on a wide-open crossing pattern and fell at the Buffalo 36. Stewart spiked the ball to stop the clock. Six seconds remained. Stewart went to the sideline. They ordered the Hail Mary play they practiced every Thursday. Four receivers line up, three on one side of the field, and they sprint to the end zone. Westbrook, with his 6-foot-4 frame and 44-inch jump reach, was supposed to leap and tip the ball into the air to a waiting teammate. Only one problem.

In practice, it never worked.

“I was like, ‘This is something beyond my understanding,’” Stewart said recently. “I’ve never been in this place before.”

Actually, he had. At the end of the first half, with Colorado leading 14-9, Colorado tried the same play. However, Westbrook ran into receiver Rae Carruth and they both fell. Stewart’s 56-yard bomb was intercepted in the end zone.

At halftime, Neuheisel got the receivers and Stewart around a blackboard and tweaked the play. He had Westbrook, in the slot, run around Carruth who broke inside. By doing that instead of both going vertical, they had free releases and avoided each other.

“As fate would have it, by running that play at the end of the first half, it was the only time in my career – and how many years have I coached? – that we ever fixed a Hail Mary play,” Neuheisel said.

Well, sure enough, with the game hanging in the balance, Colorado ran a second straight play drawn up like kids in a playground. Stewart ran back into the huddle and looked into the eyes of his players.

“It was a surreal moment,” he said.

Stewart, who had fumbled at the Michigan goal line with 5:08 left and down 26-14, was praying.

He told his offense one thing: “Give me a little time, fellas. Just give me a little time.”

After the Buffs broke the huddle, Westbrook did an improvisation that few know about but may have been the key to the win. As he lined up in the slot, he motioned to Blake Anderson, on his outside, to switch spots. Westbrook figured the ball was going to get tipped anyway. As the team’s top receiver threat, he had the best chance of catching it.

“That’s not the way we practiced it,” Westbrook said. “No one was going to object to what I tell them. The only one would be Kordell and he wasn’t out there. Things usually went well when I say it.”

Michigan rushed only three players. Eight others were way deep. Colorado’s wide receivers all had free releases. ABC analyst Bob Griese, a former Michigan star, referring to the wideouts said, “If I was the defense, I’d have a few more guys over there.”

The ball snapped and four Buffaloes flew down the field. Stewart dropped back. He had plenty of time but linebacker Trevor Pryce, the future Denver Bronco, appeared to get around tackle Tony Berti. Stewart was just a few feet away, bouncing on his toes, waiting for his receivers to reach the end zone. But waiting for Pryce was Rashaan Salaam who blocked him just enough for Berti to recover and knock him down.

“Rashaan Salaam wins the Heisman Trophy and the next week goes to Texas and has 300 yards and has the 2,000-yard season,” Neuheisel said. “There are a lot of plays about Rashaan Salaam I remember that exemplified his great season. But the most valuable play he made in that entire year was on that Hail Mary.”

Meanwhile, Stewart cocked his arm for the most important throw of his life. He’d thrown it 60 yards in practice. However, this time he had dropped back all the way to the 26. That’s 74 yards to the end zone. In the Big House. On national television. With Trevor Pryce breathing down his shoulder pads.

“The most important part of this whole entire sequence was they were only rushing three guys,” Stewart said. “That’s the best thing they could’ve done for us because it gave me time. All I had to do was make sure the guys in front of me were in front of me. That was the nose tackle and the right defensive end because I had to maneuver myself to get in position to throw to my left.”

As Pryce went down, Stewart, reaching back nearly to his Achilles, unleashed a leather rocket into the warm Michigan air and…

***

When Stewart, 43, sits down in the Guggenheim Geography building on the University of Colorado campus, students half his age don’t remember him as “Slash,” the quarterback who nearly revolutionized a position in the NFL. They don’t know him from his TV work with ESPN or his sports talk radio shows.

They know him from the Miracle at Michigan. When Stewart unloaded that pass, few of his classmates were alive.

“They find out who I am and go, ‘I knew it was you! My dad loved you!’” Stewart said.

Stewart laughed. He was talking from Boulder where he has returned to get the last three credits for his degree in communications. It’s not that he needs it. The website CelebrityNetWorth estimated his net worth last year at $16 million. He already has a resume dotted with media jobs. The degree is a gift to himself and also a message to his 13-year-old son, Syre.

“It’s finishing,” Stewart said. “It’s an accomplishment. My son gets a chance to see his dad finish school at a late age. Very seldom does a kid get to see his parent go to school. He’s an A/B student. I just want to make sure that, one, I get it done, and two, I want my baby to see that.

“It’ll be great for his confidence.”

Syre has seen plenty of his father in the NFL. So has most of America’s sports fans. Back in the mid-’90s, Stewart was the No Fun League’s lone cover boy for innovation and progress. Drafted as a wide receiver in the second round, he became the Pittsburgh Steelers’ most versatile weapon. He lined up at receiver, quarterback and running back, using coordinator Chan Gailey’s innovative formations and playbook. Stewart scored receiving, passing and running. He was the Renaissance artist on a franchise built by house painters. In his three years under Gailey, the first when Gailey was receivers coach, Stewart ran for 20 touchdowns, passed for 23 and caught five more.

Slash, as in receiver slash quarterback slash running back, was born.

“When I got into the league, my style of play wasn’t accepted,” Stewart said. “They thought I should play another position. I was one of the most electrifying players in the league when I was doing it.”

He helped lead the Steelers to the Super Bowl his rookie season. His agent, Leigh Steinberg, talked about a whole ad campaign based around the concept of Slash. At the Super Bowl, Stewart bought Neuheisel tickets.

“He had all the things you want in terms of arm strength,” Neuheisel said. “He had the charismatic personality to be the leader in the huddle. I think if someone thought outside the box as Chan Gailey did when they called him Slash, I think Kordell would’ve been even more fun.”

But Gailey left after the 1997 season to be head coach in Dallas and Stewart was never quite the same. In his last five years in Pittsburgh, he averaged 2,025 passing yards while compiling 48 touchdown passes and 53 interceptions.

“If they’d kept Chan there, shoot, I’d have been great,” Stewart said. “Everything changed. They tried to make me something I wasn’t. They were afraid of a mobile quarterback. They tried to make me sit in the pocket all day. That’s not my style. Let [Ben] Roethlisberger sit in the pocket all day.”

One theory former teammate Plaxico Burress circulated around the league was a rumor about Stewart’s sexual orientation; that greatly affected him. Burress said, “He was never the same after that.” Stewart, who married the granddaughter of Civil Rights leader Hosea Williams in 2011, divorced in 2013.

Looking back, Stewart who addressed the issue in the autobiography he released in March, “Truth: The Kordell Stewart Story,” admits the rumors took their toll.

“It had an effect on me,” he said. “If it wasn’t success, that became the blame why it didn’t happen. Everything I did was magnified times 10 whether I liked it or not.”

Stewart wound up warming the bench in Baltimore and Chicago before getting cut in 2005. Despite his career going steadily downhill, he still stands fourth on the NFL’s all-time list for rushing touchdowns by a quarterback with 40. The NFL Network listed him sixth among the top-10 most-versatile players of all-time.

He took those credentials to ESPN where he was a college football analyst then did stints as a sideline reporter for the now-defunct UFL and as analyst on “NFL Live,” “NFL 32,” “Take Two” and “Mike & Mike in the Morning.” ESPN didn’t renew his contract and he found a soft landing in talk radio in 2012 with a show on Atlanta’s WZGC-FM, 92.9 The Game.

On his current show, “No Huddle” on TuneIn Radio from 4-7 p.m. ET (844.635.6884 to call in), Stewart has lambasted the Broncos for not giving Von Miller what he’s worth (“Suh, Cox are getting $52-65 million guaranteed and Von Miller is only getting $38.9?” he said) and weighed in on concussions (he has shown no lingering effects). In other words, he’s having as much fun as he did when he threw for three touchdowns to beat the Broncos in 1997.

“In TV you just have to stay pretty,” Stewart said. “In radio you can be pretty but they don’t see you. You just need a good voice. In radio, the pay is just as good, if not better, and it’s long term.”

While Stewart was catching, passing and running, Westbrook was mostly sitting. Drafted fourth overall by Washington in ’95, Westbrook suffered injuries throughout his career. He had a broken neck fused with a plate and four screws, a screw in his right wrist, two screws in his left knee, fractures to his fingers and a couple of concussions.

“I could go on,” said Westbrook, now 44. “Sometimes I have memory problems. I don’t know if I chalk that up to old age or running into linebackers.”

He retired in 2002 with still credible numbers: 285 catches for 4,374 yards and 26 TDs. But he may be best known for a savage beating he gave fellow receiver Stephen Davis during a practice in 1997. The fight began with some innocent discussions among receivers about who had the best hands. It quickly dissolved into a shot at Westbrook dropping a ball the previous week and his two Lamborghinis and big house.

“I said, ‘You’re just jealous,’” Westbrook said. “He said instantly, ‘I don’t care about your house and your cars. You saying I’m jealous sounds gay.’ I punched him in the face. Then I punched him six more times.”

The problem is Davis didn’t use the word “gay.” He also said that to an NFL player who started taking martial arts lessons his second year in the league. He said it in front of TV cameras. Nice timing, Stephen. Westbrook, always a fan of martial arts movies as a kid, became attracted to the UFC when it began in 1992, his sophomore year at Colorado.

He also noticed those specializing in jiu-jitsu hardly ever lost. He saw Royce Gracie, a 178-pound guy and one of the trailblazers, beating guys 280, 300 pounds.

“I immediately thought, ‘I have to learn that,’” Westbrook said. “In 1996 I started looking for it. I’m a competitor. I do believe there’s a certain plateau you reach as a competitor and you can’t get any more. Like me, like Michael Jordan, like guys who are so competitive, whether it’s ping pong, jump rope, I don’t care. I have to win. If I’m not good at it, I’m going to go get good so I can beat you at it. I’m not walking around here and this little dude can whoop me because he knows that and I don’t.”

He started training in taekwondo and became good using kicks and punches and elbows and knees. “Stephen Davis ran into that,” Westbrook said.

However, Westbrook wanted to learn Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, which is ground fighting with an emphasis on pressure points. The emphasis is on submission holds rather than brute force. Westbrook not only found an alternative competitive outlet but also an inner peace he never found in the NFL or growing up in inner-city Detroit.

“If I had trained in jiu-jitsu, that fight would have never happened,” he said. “Jiu-jitsu does two things to you: It gives you so much confidence knowing that it’s going to be rare that you’ll find a guy who can really challenge you in a fight. Two, it calms you down so much because of that fact.”

Westbrook wound up with a black belt in jiu-jitsu and one of Davis’ biggest supporters. He has walked away from more fights than he can count. His MMA career ended after three fights. He was 1-1 with one no contest. He has three children, a degree in psychology and he put a lot of his NFL money into a 401K and an annuity. He is financially independent and has owned Michael Westbrook’s Self-Defense Academy in Gilbert, Ariz., for nine years.

Walking away from MMA was easier than walking away from the NFL and not because he was healthy.

“I don’t want to be in a place where I have to punch someone in the face and then come down off of that and pick up and play with my kids,” Westbrook said.

***

… as the ball floated in the deep blue sky, Westbrook ran down the field more laboriously than anyone knew. He had been plagued with cramps since the second quarter. Severely dehydrated, he had an IV at halftime. But he could run 64 more yards.

As the ball began its descent, Westbrook had to judge where it would land. He decided it would be between the 5 and the goal line.

“Everything was completely in slow motion,” he said. “They say that and it’s so true. It was like taking all day. It seemed like the ball was in the air for five hours. I was looking, picking my way through, trying to find a good spot. And it was so weird.

“No one was defending me.”

True. The whole Michigan defense was looking in the air. Westbrook had drifted along the outside and then behind the pack. No one stood behind him. Westbrook was a 25-foot long jumper and 11-foot standing long jumper.

“All I [had] to do is start jogging,” he said. “Fortunately, it wasn’t even tipped that far away. I did a drop step and jumped.”

Anderson, who forever more would be nicknamed “Tipper,” out-jumped the entire world and got his hand on it. It went backward.

“I saw [cornerback] Ty Law,” Westbrook said. “Guess what he was doing: Looking at the ball. It was tipped and he turned to follow the ball. I was behind everybody.”

The ball landed in his arms right before he landed in Law’s. They both fell in the end zone. Law got up; Westbrook did not. He was mobbed by the entire Colorado roster, including Stewart who, when he finally cut through the humanity, told Westbrook, “I love you.”

Westbrook: “I love you, too.”

Meanwhile, Neuheisel found stunned Michigan coach Gary Moeller walking across the field. If looks could kill, Neuheisel never would have gone on to be the head coach at Colorado the next year or Washington and UCLA after that.

“He gave me the worst death stare I’ve ever been given in my life,” Neuheisel said. “The glare, the hatred, he was so hurt by the moment. He wasn’t mad at Rick Neuheisel. He was just mad the game had gotten away. I remember feeling horrible and stopping. Like, I should show more class. Then I go, ‘To hell with this!’ and ran down to the pile myself.”

I never saw the play. I saw only Stewart’s throw and then a sideline of white jerseys jumping up and down. Michigan secondary coach Billy Harris got a good view. He harangued each and every defensive back in the locker room, yelling, “You lost this game for me!”

The lessons taken away from this epic finish have permeated sports for generations. A pack of Buffaloes, 22 years after they stopped leaping on the Michigan Stadium end zone, still believe in it.

“Anytime you have time, you have hope,” Stewart said. “I wasn’t in any position to wonder if it would happen or not. I just threw it as far as I could.”

Maybe it was luck. Maybe it was fate. Maybe Michigan was overrated all along. But the game had an epic impact on the teams’ season. Michigan stumbled to an 8-4 record, beating Colorado State in the Holiday Bowl but finishing only 12th in the AP poll. Moeller resigned that May after video tapes showed his drunken outburst over an arrest for disorderly conduct. Colorado went 11-1, losing only at Nebraska, destroying Notre Dame in the Fiesta Bowl and finishing third in the ranking. McCartney retired to concentrate on his Promise Keepers ministry where he still works to this day.

In Promise Keepers, he encourages men to be more than they can be, much as he did his players on the sideline before the Miracle at Michigan grew capital letters. He sold the players all year. With the last note of the Michigan band long gone silent, and the lone sounds among 100,000 stunned souls were the screams from 100 Colorado players and staff, he had made believers.

Forever.

“After every victory, we’d celebrate by singing the fight song,” McCartney said. “When we sang the fight song in Ann Arbor that day, we sang loud enough for everybody in Ann Arbor to hear.”

John Henderson, who covered Colorado football from 1990-94 and 2011-13, is a freelance writer based in Rome. Read his travel blog, Dog-Eared Passport, at www.johnhendersontravel.com.