This story originally appeared in Mile High Sports Magazine. Read the full digital edition.

These were simpler times.

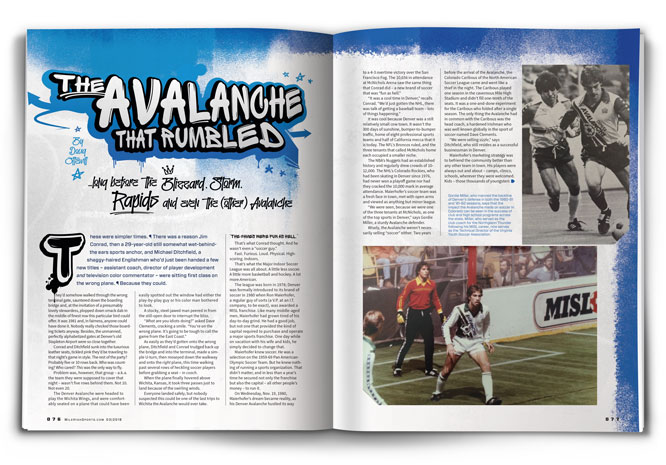

There was a reason Jim Conrad, then a 29-year-old still somewhat wet-behind-the ears sports anchor, and Michael Ditchfield, a shaggy-haired Englishman who’d just been handed a few new titles – assistant coach, director of player development and television color commentator – were sitting first class on the wrong plane.

Because they could.

They’d somehow walked through the wrong terminal gate, sauntered down the boarding bridge and, at the invitation of a presumably lovely stewardess, plopped down smack dab in the middle of finest row this particular bird could offer. It was 1981 and, in fairness, anyone could have done it. Nobody really checked those boarding tickets anyway. Besides, the unmanned, perfectly alphabetized gates at Denver’s old Stapleton Airport were so close together.

Conrad and Ditchfield sunk into the luxurious leather seats, tickled pink they’d be traveling to that night’s game in style. The rest of the party? Probably five or 10 rows back. Who was counting? Who cared? This was the only way to fly.

Problem was, however, that group – a.k.a. the team they were supposed to cover that night – wasn’t five rows behind them. Not 10. Not even 20.

The Denver Avalanche were headed to play the Wichita Wings, and were comfortably seated on a plane that could have been easily spotted out the window had either the play-by-play guy or his color man bothered to look.

A stocky, steel-jawed man peered in from the still-open door to interrupt the bliss.

“What are you idiots doing?” asked Dave Clements, cracking a smile. “You’re on the wrong plane. It’s going to be tough to call the game from the East Coast.”

As easily as they’d gotten onto the wrong plane, Ditchfield and Conrad trudged back up the bridge and into the terminal, made a simple U-turn, then moseyed down the walkway and onto the right plane, this time walking past several rows of heckling soccer players before grabbing a seat – in coach.

When the plane finally hovered above Wichita, Kansas, it took three passes just to land because of the swirling winds.

Everyone landed safely, but nobody suspected this could be one of the last trips to Wichita the Avalanche would ever take.

***

“The games were fun as hell.”

That’s what Conrad thought. And he wasn’t even a “soccer guy.”

Fast. Furious. Loud. Physical. High-scoring. Indoors.

That’s what the Major Indoor Soccer League was all about. A little less soccer. A little more basketball and hockey. A lot more American.

The league was born in 1978; Denver was formally introduced to its brand of soccer in 1980 when Ron Maierhofer, a regular guy of sorts (a V.P. at an I.T. company, to be exact), was awarded a MISL franchise. Like many middle-aged men, Maierhofer had grown tired of his day-to-day grind. He had a good job, but not one that provided the kind of capital required to purchase and operate a major sports franchise. One day while on vacation with his wife and kids, he simply decided to change that.

Maierhofer knew soccer. He was a selection on the 1959-69 Pan American-Olympic Soccer Team. But he knew nothing of running a sports organization. That didn’t matter, and in less than a year’s time he secured not only the franchise but also the capital – all other people’s money – to run it.

On Wednesday, Nov. 19, 1980, Maierhofer’s dream became reality, as his Denver Avalanche hustled its way to a 4-3 overtime victory over the San Francisco Fog. The 10,656 in attendance at McNichols Arena saw the same thing that Conrad did – a new brand of soccer that was “fun as hell.”

“It was a cool time in Denver,” recalls Conrad. “We’d just gotten the NHL, there was talk of getting a baseball team – lots of things happening.”

It was cool because Denver was a still relatively small cow town. It wasn’t the 300 days of sunshine, bumper-to-bumper traffic, home of eight professional sports teams and half of California mecca that it is today. The NFL’s Broncos ruled, and the three tenants that called McNichols home each occupied a smaller niche.

The NBA’s Nuggets had an established history and regularly drew crowds of 10-12,000. The NHL’s Colorado Rockies, who had been skating in Denver since 1976, had never won a playoff game nor had they cracked the 10,000 mark in average attendance. Maierhofer’s soccer team was a fresh face in town, met with open arms and viewed as anything but minor league.

“We were seen, because we were one of the three tenants at McNichols, as one of the top sports in Denver,” says Gordie Miller, a sturdy Avalanche defender.

Wisely, the Avalanche weren’t necessarily selling “soccer” either. Two years before the arrival of the Avalanche, the Colorado Caribous of the North American Soccer League came and went like a thief in the night. The Caribous played one season in the cavernous Mile High Stadium and didn’t fill one-tenth of the seats. It was a one-and-done experiment for the Caribous who folded after a single season. The only thing the Avalanche had in common with the Caribous was the head coach, a hardened Irishman who was well known globally in the sport of soccer named Dave Clements.

“We were selling sizzle,” says Ditchfield, who still resides as a successful businessman in Denver.

Maierhofer’s marketing strategy was to befriend the community better than any other team in town. His players were always out and about – camps, clinics, schools, wherever they were welcomed. Kids – those thousands of youngsters who grew up playing soccer – knew his players. Maierhofer boldly went head to head with the Rockies and Nuggets using advertisements that promised more excitement and cheaper concessions.

Following the 1979 NFL season, Broncos owner Edward Kaiser mysteriously disbanded the extremely popular Denver Broncos Cheerleaders. Debbie LaPorta, a member of the cheer team, came to Maierhofer to see if he might be interested in putting together a squad made up of girls who suddenly didn’t have a team to cheer for. Naturally, he loved the idea and the “Snow Cats” were born.

Besides their efforts in the community, the product on the turf was a damn good one.

“The games were great,” recalls Duncan MacEwan, an English transplant who’d played college soccer at Penn State. “There was music. The fans were right on top of us.

“It was a big show, a night out.”

Fans didn’t have to understand soccer to enjoy the Avalanche. That was important. The game itself was new, so the learning curve was the same for everyone. It was fun, not stodgy and intimidating; it was not the same game that only Europeans were educated enough to enjoy. “Missile” soccer was action-packed and filled with goals – 10 or more for the winning side was not uncommon. As Ditchfield, a soccer purist by his own admission, so aptly put it, “This was human pinball.”

Following games, the entire team, its executives and the Snow Cats would host after-parties that regularly saw 1,000 fans tag along to whatever local establishment was willing to provide complimentary food and drink for the team. Every local news station showed game highlights, no different than the Nuggets or Rockies. Ten games in the inaugural season were broadcast live on Denver’s Channel 2, where Conrad and Kyle Rote Jr., who preceded Ditchfield as the color analyst, enlightened an intrigued local television audience.

Like so many teams before and since, the Avalanche took advantage of Denver’s thin air and 5,280 feet of elevation. At home, despite being one of the youngest teams in the MISL, the Avalanche was nearly unbeatable.

“Denver was an anomaly – young, mostly North American and very fit,” explains Miller. “It almost seemed like North American players adapted quicker to the indoor game because we’d played basketball or hockey growing up, and Denver was made up of a lot of American players.

“We played a run-and-gun style that wore down the opponent. When we came into the league not many people thought we’d be good, but we just outworked teams, especially at home.”

Adds MacEwan: “And we had oxygen on the bench.”

The MISL had something else in its favor, too. The NASL, which debuted in 1968 and featured the likes of global soccer legends Pelé, Franz Beckenbauer, Carlos Alberto and Georgie Best, was beginning to show cracks. The league had notably paid its players large salaries and was beginning to experience financial issues. NASL teams were starting to dissolve and the MISL became a logical home for a bevy of American and international talent. Miller, who had played for the NASL’s Toronto Blizzard in 1979, was one such example.

“MISL was high-level soccer,” he says.

NASL rules also dictated that every team must employ a minimum number of North American players. Miller says the division between international stars and North American players was palpable and sometimes problematic. In the MISL, no such rules existed, so teams simply fielded the best players they could sign (at greatly reduced salaries by comparison).

“It’s not a knock on current indoor soccer leagues, but the level of [indoor] play is nowhere near where it was in the MISL,” says MacEwan. “The top players today go overseas or play in MLS. [Back] then, a lot of very good players chose the MISL.”

In Denver, there was very little to not like about Avalanche. At nearly 8,000 fans per home game in the 1980-81 season, the Avalanche were fourth in the MISL in attendance. Despite missing the playoffs, things were looking up in Denver; Maierhofer’s dream had unquestionably become a reality.

Says Conrad: “I thought that’s what soccer in the United States would become.”

***

“It was a blast,” Miller says today from his office as the Technical Director of the Virginia Youth Soccer Association. “We were just a bunch of young guys getting paid to play a game we loved.”

In the 1981-82 season, the Avalanche’s second, they played well enough to earn a spot in the MISL postseason. Oddly, they’d enter the playoffs without one of their best players, Adrian Brooks.

With fans continuing to support the Avalanche, a coach who had been honored as the 1981-82 MISL Coach of the Year and a postseason berth in just its second season, there was no question that Maierhofer’s team was perceived as “major” in Denver. But Maierhofer was about to experience his first major league problem.

Brooks, the MVP of the 1981 MISL All-Star Game played in Madison Square Garden, had a somewhat bizarre contract situation. The terms of his deal with the Avalanche only went through the regular season, technically expiring before the postseason began. While both parties knew of the situation and met regularly to rectify it, no agreement was reached. Thus, nothing was inked and a healthy Brooks sat out of the playoffs. The Avalanche were unceremoniously swept in the first round by the St. Louis Steamers, who went on to win the Western Division but lose to the New York Arrows in the MISL championship series.

In reality, Brooks’ contract situation was merely the first public problem experienced by the Avalanche. Behind the scenes there were bigger issues. In his book “No Money Down – How to Buy a Sports Franchise,” Maierhofer offers the gory details of the demise of his beloved Avalanche. In summation, the team’s investment group had under-capitalized and over-projected the Avalanche. To the naked eye, Denver’s “fourth” franchise appeared to be extremely viable, but in retrospect, Maierhofer’s team might have been doomed from the beginning.

Ultimately, MISL officials allowed Maierhofer’s group to retain the rights to the Avalanche, but chose to move on without scheduling them into the ’82-83 season. Though the plan was to return to play in 1983, a chapter 11 bankruptcy settlement ultimately resulted in the sale of team assets and a move to Tacoma, where much of the Avalanche roster was retained.

“When it was announced that the team was not going to compete,” says Ditchfield, “we all were surprised. We drew crowds. It seemed financially sound.”

Says Miller: “We felt it would take off.”

Tallying just one more season than the Caribous, the Denver Avalanche had come and gone.

But the Avalanche did leave a mark.

Today, Colorado is widely considered a hotbed for young soccer talent. From top to bottom, it’s one of the best places for soccer in America. Giltedgesoccer.com conducted a nationwide marketing study in 2016 that considered soccer TV viewership, attendance, participation, social conversation and digital search; the study concluded that Denver/Boulder was the No. 7 market in the United States.

There’s a reason for that, suggests Miller.

“Across the country, really, you see some of the best soccer markets are ones where MISL teams once existed,” he says. “Players from those teams gave a lot to the community in the offseason and kids watched them play during the season. Denver is a great example.”

After his four-year career in the MISL, Miller returned to Denver where he became the “club coach” of the Northglenn Thunder, a competitive soccer club that fielded teams ages 10 and up. But he wasn’t the only one. He’s still able to rattle off a list of teammates who did something similar.

Kelvin Norman and Pascal “Frenchy” Antoine, Aurora Sting. Mike Freitag, Director of Coaching for Colorado Soccer Association and former assistant coach at DU. Michael Ditchfield was the Director of Player Development for the NASA club in Thornton. Mike Haas is now the Technical Director of Colorado Storm. Frank Bucci, an Avalanche goalie, conducted goalkeeping camps all over Colorado. Chelo Curi was with the Cherry Creek Lightning; now he’s been at Cherry Creek High School for 19 years as the school’s head boys’ coach, winning a state title in 2010. Peter Horvath became the head coach of the Columbine High School boys’ and girls’ soccer teams. Over the 26 years he spent coaching the two teams, Horvath compiled a combined 597-174-49 record. The boys’ teams won three state championships, and finished runner-up three times. The girls’ team finished state runners-up five times. Horvath retired in 2009 and from 1989 to 1991 served as president of the Colorado High School Soccer Coaches Association. His son Ethan currently plays in Europe and has enjoyed call-ups with the USMNT.

“The Denver Avalanche made a dent,” says Conrad. “They made an impression.”

Not only did the Avalanche influence generations of players that followed, they scratched an itch that Denver has to this day. The Colorado Rapids are a prime example. An MLS charter organization, the Rapids are set to play in their 23rd season. Their home games are played at a beautiful, soccer-specific stadium and they won the MLS Cup in 2010.

This past December, the Colorado Blizzard, a local club that had previously competed in Colorado Springs, made its debut as a Major Arena Soccer League 2 (M2) expansion team. When tryouts were held, more than 120 hopefuls showed up. The Blizzard plays its games at the Denver Coliseum, and with a 7-2 record in tow and home crowds that have reached 2,500-plus, coach and co-owner John Wells is already thinking about making the leap to the more established MASL.

“We knew we had to be good right away,” says Wells. “Fans will only support a good product.”

As it was for Maierhofer and countless others, the risk of taking the next step up is always financial. Expenses in the MASL, says Wells, are roughly three times more. With any new professional sports team in Denver – now much more than a cow town – there’s a more than better chance that the experiment will be short-lived.

“The goal is definitely to get to the MASL,” says Wells with the same enthusiasm that Ron Maiederhofer once had.

Whether the kids who attend Blizzard games know it or not, it’s the Denver Avalanche they can thank. After all, it was that blink of an eye – two fun-filled seasons at Big Mac – that gave birth to this crazy notion that indoor soccer can, and should, be played in Denver.

“It was a great time,” says MacEwan.

“I just wish it would have lasted.”