Over the years, I’ve written many stories — too many — about the frequent post-career physical struggles of former NFL or even NCAA football players.

The much-feted 1977 Broncos, the subject of my book ’77: Denver, the Broncos, and a Coming of Age, ended up a virtual case study.

They hurt, they ache, they limp, they’ve had joint replacements, and in the case of wide receiver Haven Moses of the M&M Connection, even suffered a stroke. (When you watch the other half of the Connection, Craig Morton, walk … you limp.)

It’s so typical, and it isn’t even close to being all CTE/concussion related.

You play football long enough, or in extreme cases maybe even play it at all, you’re going to pay the price.

That’s indisputable.

It’s back in the spotlight this week, with the opening of the potentially landmark Ploetz vs. NCAA in Dallas. Greg Ploetz, the former Texas defensive end who spent much of his childhood in Colorado Springs, after his 2015 death was found to have Stage 4 CTE. His widow, Deb, is suing, with Greg’s estate as the other plaintiff. I was subpoenaed and deposed in the case because I had interviewed Greg in 2001 for Horns, Hogs, and Nixon Coming. And there’s going to be plenty more (cases) where that came from.

That and the other cases, including the NFL settlement with former players, are about financial liability.

But beyond that, shouldn’t football be the last resort for good athletes?

I’m not saying ban it, since the liability issue might even take care of that — especially at the grassroots levels.

I get football’s allure. I’ve written about it, been around it and even played it, proving you don’t have to be good to require major knee surgery. My father played for a Helms Foundation national championship team at Wisconsin, then coached at the college and NFL levels.

I’m a fan, too.

But the most aggravating thing about the continuing revelations and mounting evidence of the potential toll is the denial involved. Regardless of how increasingly enlightened those in the sport become about attempting to minimize the risks, it always will be perilous.

Understand that? Willing to accept the risks for the enjoyment … and, perhaps at higher levels, the money?

Fine.

But especially NFL players continue to act as if they’ll be the lucky ones with immunity to the perils as team alumni hobble on the sideline when visiting practices should induce shakes of the head. In many cases, yes, physical realities help dictate the decisions, since there are few 280-pound centerfielders.

Frankly, I’m surprised football hasn’t suffered more collateral damage than it has the past, say, 20 years as the evidence mounts.

Equipment, including helmets, is better, but that isn’t the panacea. I thought the sport would be in huge trouble, not just under fire and sweating liability issues and losing participatory numbers.

The game has been affected, no question, and I actually think it’s a huge positive that good athletes no longer are as pressured or as expected to play football as in the past. Some of that is a byproduct of increased specialization in other sports at the high school level. But some of it is a realization that it’s bad parenting to force or pressure kids to play football if they don’t love it. It shouldn’t be like piano lessons.

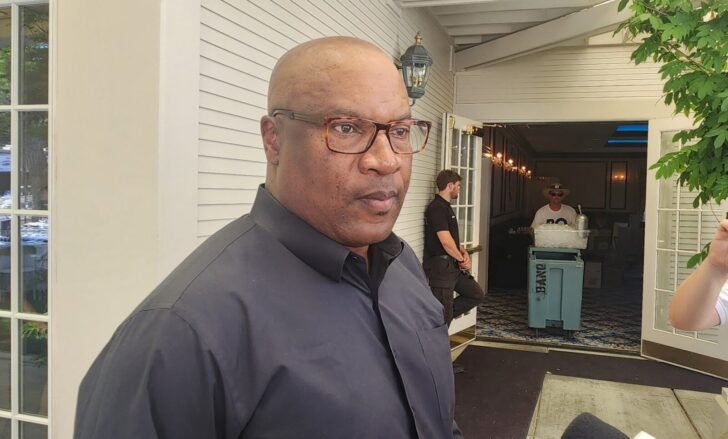

Bo Jackson looks at a replica of his bobble head that was given away to fans before the game between the Chicago White Sox and the Detroit Tigers at U.S. Cellular Field. Mandatory Credit: David Banks-USA TODAY Sports

Bo Jackson, pictured at the top and at right, was an elite talent in both football and baseball. He played four seasons, from 1987 through 1990, with the Raiders, rushing for 2,782 yards on 515 carries. A hip injury ended his football career, but he later said he was planning to step away from the sport to concentrate on baseball, in part for family reasons, anyway.

He ended up playing eight seasons in the majors from 1986 to 1994 (with one season off), with the Royals, White Sox and Angels, hitting .250.

Was he a “better” football player? No question. But if he’d focused on baseball sooner and stayed healthy, he would have been an all-time great.

Imagine how long he could have played baseball if he’d stayed away from football.

This was a while ago, but I played high school baseball at Wheat Ridge with Dave Logan, one of the two men who were drafted by NFL, NBA and MLB teams.

We were the infamous Logan & Frei battery, setting me up to lead the state in passed balls.

Baseball was clearly his third sport, but that was more about time invested than aptitude and talent, and I’m convinced that if Logan had shut it down in basketball and football and focused only on baseball after the Reds drafted him in 1972, or played college baseball only (wherever it was), he would have gotten to the majors. Instead, he went on from CU to an NFL career, mostly with the Browns.

(I’d run the Wheat Ridge team picture here … but, oh, the hair.)

The negative about baseball for impatient young men then was and now is the accepted inevitability of having to come up through a farm system.

But if you’re good, you make terrific money, you can have a long career … and you can walk when you’re 55.

That beats the hell out of football.

Of course, the percentage of those who play the sports as youths becoming pros is tiny, so maybe that’s a red herring in this discussion.

But for other reasons, too, I don’t understand why more parents aren’t saying: Anything but football, son.

Terry Frei of the Greeley Tribune writes two commentaries a week for Mile High Sports. He has been named a state’s sports writer of the year seven times, four times in Colorado and three times in Oregon. He’s the author of seven books, including “Third Down and a War to Go” and “’77: Denver, the Broncos, and a Coming of Age.” His web site is terryfrei.com. His Mile High Sports commentary archive and additional “On the Colorado Scene” commentaries are here. His major Greeley Tribune pieces can be accessed here.

E-mail: [email protected]

Twitter: @tfrei