A perfect game. A postseason no-hitter. Enshrinement in Cooperstown. Two Cy Young Awards.

Before all that, the late Harry Leroy Halladay III was just a quiet kid from the Denver area who loved baseball and impressed his coaches as a hard worker and a loyal teammate.

Local baseball guru Bus Campbell mentored 115 pitchers who wound up in the big leagues over his half-century of coaching in Denver. “Doc” Halladay was the best of the bunch by far.

“A lot of kids don’t understand what mentality you need to have, and he did at 15 and 16 years old,” said his high school coach, James Capra. Halladay, a native of the Denver suburb of Arvada, became enamored with baseball early in his life.

His upbringing was strict, and he spent most of his free time playing sports. Roy Senior, a commercial pilot, contacted Campbell early on to help harness Roy’s potential on the mound.

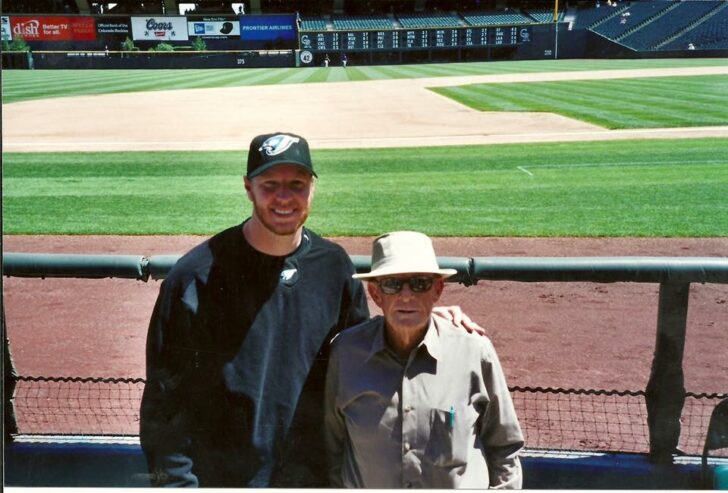

“Bus Campbell was his greatest influence and acted as a grandfather of sorts,” said Halladay’s sister, Heather. “Bus was everything to Roy from high school to the major leagues.”

Campbell helped Roy develop from a lengthy thrower into a clear-cut ace by the time he started high school at Arvada West in the fall of 1991.

The Wildcats ballclub had a solid rotation during Halladay’s freshman season, but his skillset forced the hand of head coach Jim Capra, who inserted him into the starting rotation at the ripe age of 15. Halladay did not lose a game in his rookie season and fell in love with the sensation of winning along the way.

Halladay won all but one of his starts during his high school career and was the ace of the Wildcats’ 1994 state championship team. His lone loss came when three Wildcats missed a game for a variety of reasons during his senior year. If the team would have been at full strength, Halladay would have likely finished high school with a flawless record.

After experiencing success during his high school career, Halladay became even more enamored with baseball. When he was not studying for school, he was studying baseball. Halladay became a student of the game, and in school terms, was taking honors courses in pitching.

He would scour through pages of Nolan Ryan pitching guides and game tape in pursuit of any which way he could gain a fair, competitive advantage.

Roy never cut corners and was determined to earn his success on merit.

“He was really advanced in his thinking and maturity level,” Capra said.

For as humble as Halladay was off the field, the moment he stepped on the mound, his sole goal was to dominate his opponent. Not only did Halladay outperform his competition, he also out-thought them.

Halladay’s dedication to success was fierce, and he would stop at nothing to be the best version of himself on the mound.

“What I saw from him was the ability to transition from being that guy – the friendly, funny, goofy guy – to this absolute bulldog when he got out on the mound,” local scout Ed Henderson said. “It was Jekyll and Hyde. I remember having a conversation with opposing players about Roy and, some of them didn’t quite understand that what they saw off the field was not what they were going to get on the field. In 28 years of doing this, I’ve never seen anybody do what he did.”

Henderson has been intertwined with Colorado baseball for nearly 30 years and was a scout for the Florida Marlins when Roy was at Arvada West. While Halladay was best known for his performance on the diamond, he was also a stud on the court, earning All-Conference honors for basketball while also running cross-country.

And though Halladay was self-motivated, he was not egotistical. His teammates were like brothers to him, and he played with his heart on his sleeve in each and every game for them.

Halladay grew up playing with the same set of kids for a majority of his life, and he developed a loyalty to them. Instead of playing for fancy club teams and traveling across the country, Halladay opted to stay local most times, playing for A-West beyond the spring into the summer.

“He was all about Arvada West,” Capra said. “He didn’t care about playing for club teams. He didn’t care about statistics. He never asked, ‘How many strikeouts do I have? How hard was I throwing?’”

For as good as Halladay was in high school, he did not let his success get the best of him.

By the time he reached his junior season, it was apparent Halladay would be able to turn his passion into a career. Still, even with his professional career on the horizon, Roy never let the limelight take control of him.

“If you compare that to kids now, they want to know how many scouts are in the stands and how many offers they are getting. That just wasn’t him,” Capra said.

Halladay led a simple life before the glitz and glamour took hold when he entered the big leagues, and that lifestyle continued by the time he cashed his first professional contract.

Going pro and the perks that come with being a big-league ballplayer were exciting opportunities heading Roy’s direction when he was 18 years old.

Halladay had committed to Arizona, but he had no intention to play for the Wildcats. All he wanted to do was have fun with his buddies while he had the chance. Despite being a top pitching prospect in the 1995 draft, Halladay opted to play for the Arvada West summer team while negotiating his contract with the Toronto Blue Jays.

He pitched once a week for his school despite his draft status. Such actions are unheard of in today’s baseball landscape.

“That’s what separates him from a lot of other players,” Capra said. “His mentality and being able to keep everything within a perspective and being humble with what is going on.”

Halladay was one of the top pitching prospects in the 1995 draft class and was expected to be a first-round pick, which meant he would be entitled to significant financial compensation.

Nowadays, most high-profile prospects in all sports have gigantic parties on draft day to celebrate their accomplishments, and the start of a new, better life. Instead of having a massive event, Roy opted for a subtle gathering on the day of the 1995 MLB draft joined by his family, teammates, and coaches.

Halladay was eventually drafted with the 17th overall pick by the Toronto Blue Jays and left the suburbs of Denver for the largest city in Canada, Toronto.

Halladay’s career got off to a rough start. After posting an earned run average over 10 in 2000, he was demoted to Single-A to start the 2001 season. “Doc” had gone from the top of the food chain in Colorado to the cellars of Major League Baseball, depths from which most young players do not typically return.

Instead of letting the demotion get the best of him, Halladay used it to his advantage to reinvent himself as a pitcher. He relied on the Blue Jays coaching staff, but also his family back in Colorado to help him regain his confidence on the mound.

Halladay would converse with his mentor, Bus Campbell, regularly when he was in the minor leagues. The two would talk about anything from Roy’s pitch repertoire to how things were back home.

While the coaches in the big leagues were critical in the beginning of Halladay’s career, it would not have been possible without the wisdom of Campbell.

The 2002 season marked the start of a new era in Halladay’s career as he returned to the big leagues with a new delivery and a fresh mindset. Halladay was an All-Star in 2002 and then again in 2003.

He was the best pitcher in the American League during 2003 and was named the Cy Young award winner after finishing the season with a 22-7 record. Halladay was an ace by the time he was 25 years old, and he only got better with age, with half of his All-Star appearances coming in the final six years of his career.

Halladay went on to win 203 games and register 2,117 strikeouts en route to a spot in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

While a vast majority of people remember Halladay for his accomplishments on the big stage, his impact on youth sports in Colorado was just as significant.

“Anybody can google his legacy on the field,” Capra said. “Everybody knows the first ballot Hall of Fame, the Cy Youngs, the no-hitters and perfect game which is over the top, but as a person and teammate, that’s the standard that is going to be hard for kids to master.”

When Halladay was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2019, he became just the second player from Colorado to earn baseball’s highest honor, joining New York Yankees relief pitcher Goose Gossage.

Colorado is not known as a hotbed for ballplayers because of how altitude affects the game. The Colorado Rockies have been unable to field a winning team consistently in part because of the altitude. When Halladay was coming through the high school system, he was unaware of the effects pitching a mile above sea level had on his pitches, which makes his success all the more impressive.

Halladay was a workhorse on the mound. In an era where pitchers rarely pitched complete games, he stood above the rest, leading the league seven times in complete games and four times in innings pitched.

He is also just one of six pitchers in baseball history to win the Cy Young award in both the American and National league, along with Gaylord Perry, Randy Johnson, Max Scherzer, Roger Clemens and Pedro Martinez.

“I think he’s the best player that’s ever come out of Colorado,” Capra said. “He’s going to be hard to match.”

Aside from Halladay and Gossage, many locals have gone on to have successful big league careers, but none have reached the heights of Halladay’s career.

There was “always a piece of Colorado with Roy,” even while he was experiencing great success in Toronto and Philadelphia. He spent the majority of his days after his playing career around the country but was planning to re-establish himself in Colorado.

Halladay never had the chance to return to Colorado as he tragically passed away in 2017 because of an aviation accident in the Gulf of Mexico. He was 40 years old and just four years removed from playing in the big leagues.

Roy always loved Colorado, and his character reflected that of a traditional native. He came from a humble background, treated everybody the same and had invested relationships with people in his community.

No matter how popular Halladay became during his life, he was always the same genuine, goofy and sensitive guy to anyone who captured his attention. Halladay may not be here today, but if he were, he would be up in the mountains fishing, hiking

and flying the great big sky.

While Halladay’s successes on the field were monumental, his legacy and positive impact on Colorado is his greatest accomplishment.